Loading...

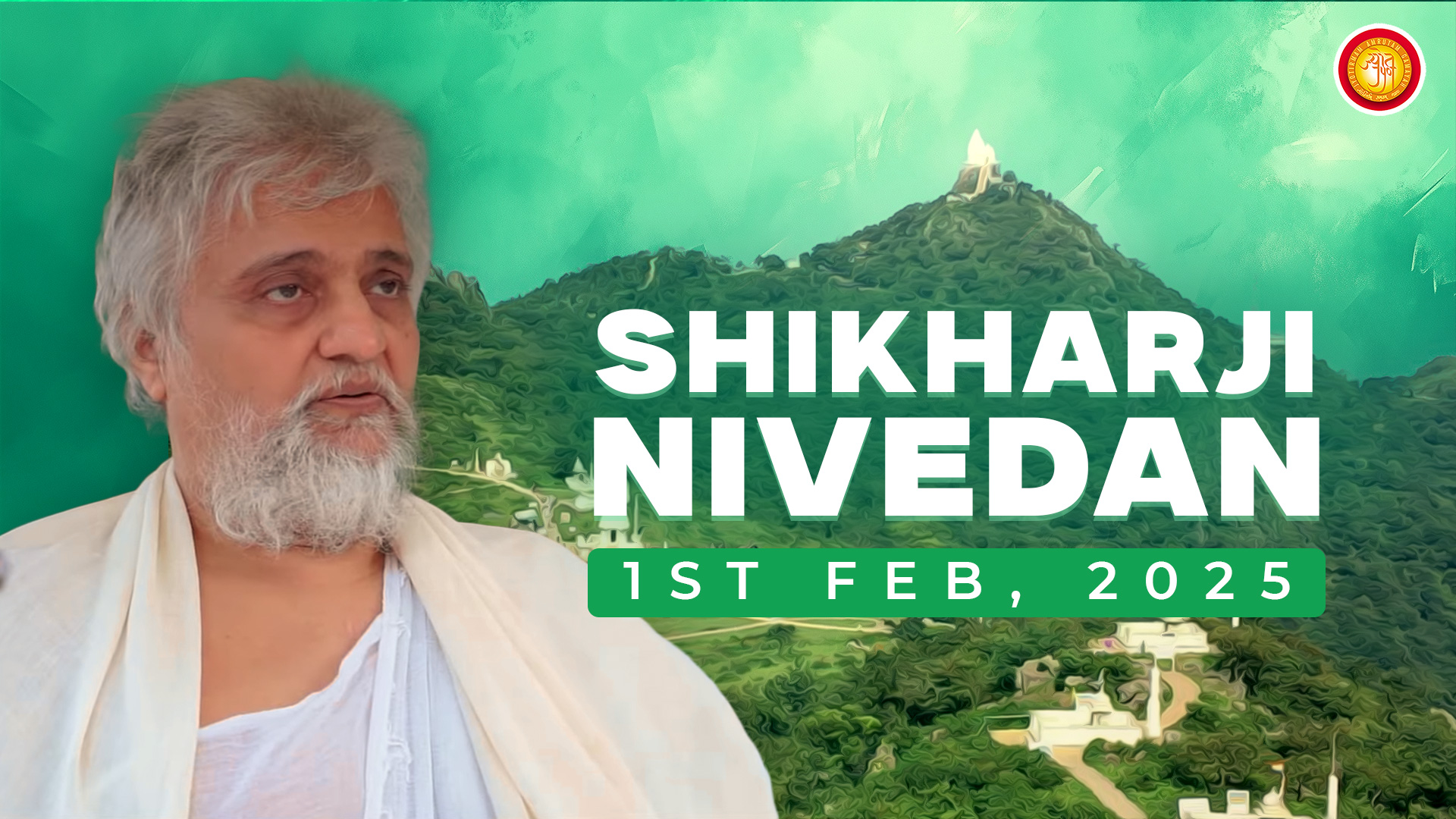

ABOUT SHIKHARJI

THE SAVE SHIKHARJI MOVEMENT

20

Tirthankaras Attained Niravan On This Hill.

“Save Shikharji Movement -2018 is one of the most prominent activities being undertaken by a large number of Jains’ all over the country and abroad.”

This movement is organized by Jyot and guided by visionary Gachchadhipati Shrimadvijay Yugbhushansuriji Maharaja. It is with respect to fresh development initiated by the existing Government’s actions which has severely affected the sanctity of the Shikharji Hill. This movement is primarily led by Jains’ of all sects (Shwetamber,Sthanak and Terapanthi) to save Shikharji Tirth from the ungodly and unjust actions of the Government against the entire Jain community.

As per this movement, Jains are pressing hard to get their most revered Shikharji Hill declared as a #PlaceOfWorship by the concerned authorities of the Government. Mecca Medina, Golden Temple, Vatican and Jerusalem are the most significant places of worship for Muslims, Sikhs, Christians and Jews respectively. In the same vein, Shikharji Thirth is regarded as the top most place of worship of Jains.

INJUSTICE TO JAINS

Although there is a clear provision under said Bihar Land Reforms Act that Govt. cannot take charge of any place of worship. Nonetheless, the govt. has unjustly acquired the hill.

LATEST NEWS

Gallery